A challenging birth for climate research

Research is not done in a flash in the best of times. Fieldwork, data analyzes and writing take time. But this time it took over ten years, two doctorates and one baby to get there.

We have just published a new article in the scientific journal Ecography. The article describes how grass and grass-like species, which are expected to become more common in a warmer climate, will affect other plants in western Norwegian pastures. This is important knowledge for understanding the effects of climate change on Norwegian nature, but the road to publication of this article has been long and tortuous.

Good start

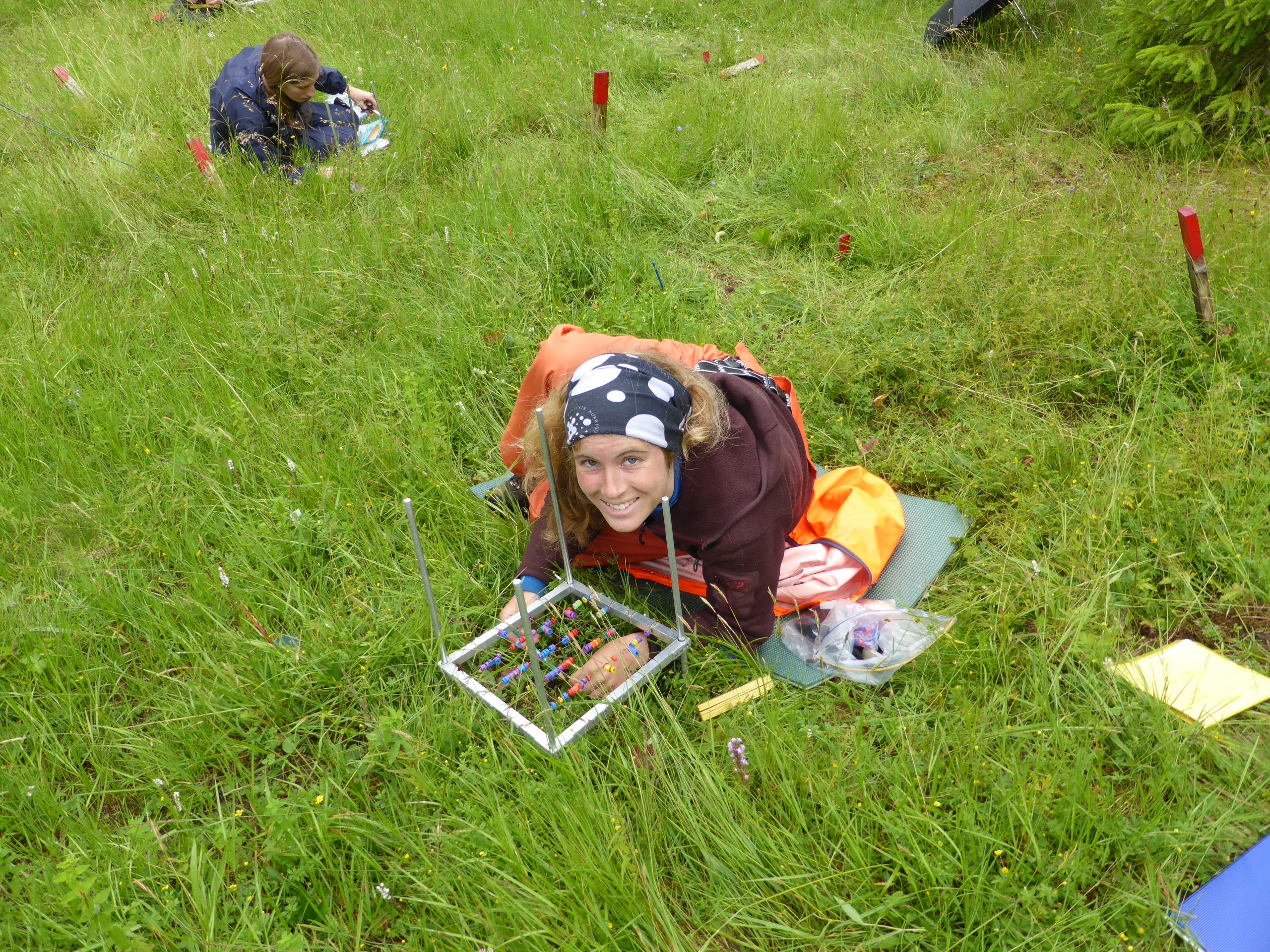

It all started fairly reliably in the summer of 2011. To find out how the grass affects other plants, we went out with scissors and paper bags and cut away grass and other grass-like plants from selected western Norwegian pastures. The idea was that if the other plants grew better without grass present, it indicated that they were held down by competition from the grass, while if, on the other hand, they grew worse without grass, it indicated that they benefited from their grass neighbors. The selected pastures varied in temperature and rainfall, so that we could compare the response under different climate conditions. Our expectation was that competition between the species would be most prominent where it was relatively warm and wet. In more extreme cold and dry climates, we expected that the plants might, on the contrary, benefit from standing close together, so that the different species might be able to protect each other from frost, drought and wind. We based this expectation on the "stress gradient hypothesis", and our research would thus contribute to an empirical test of this hypothesis.

Both the cutting of grass and registration of the remaining plants were repeated annually

In the summer of 2014, all the data were compiled and analyzed, and a first draft of a scientific article was written. It was to be part of a doctoral thesis that autumn. This is a relatively normal course of time for an ecological study. The doctorate was well received, but this particular article draft was never completed. As the last script in the thesis, it was probably treated a little stepmotherly, and the scholarship holder moved on to a new job and new tasks. But our grass was not allowed to grow in peace - the experiment was inherited.

Life happens along the way

The next graduate student went on with fresh courage, did more fieldwork, collected even more data, and spent a lot of time rewriting and improving the draft article. When it was included in doctoral degree number two in 2019, it was in a clearly improved condition. Nevertheless, the draft was again shelved before it could be published in a scientific journal. There was nothing wrong with the scientific quality, and there was not much work left, but other tasks still ended up at the front of the queue.

Time passed, and moving, new jobs and family meant that the draft article ended up further and further down the pile. But then, in 2023, the first author with a baby well on the way, it was suddenly brought up again and dusted off. Maybe we could reach the finish line after all? Intense work followed, with an absolute deadline fast approaching. And just before a new, tiny person came into the world, the manuscript draft was completed and sent to the journal. And this time it made it through!

Worth the wait?

Was it worth the wait? Definitely. This article is a piece in the big puzzle that allows us to understand how climate change affects the nature around us. But next time we will hopefully be able to reach the goal of the research without a birth as an obstetrician.