By Vendula Špačková, Applied Ecology student, CZU Prague

I am a Bachelor student of Applied Ecology at the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague. As part of my studies, I wanted to complete an internship abroad and actively searched for opportunities that would combine ecology, fieldwork, and international experience. After applying and successfully passing the selection process, I was accepted for a two-month Erasmus+ internship in Norway with the research group Between the Fjords at the University of Bergen.

The team uses the diverse landscapes of Western Norway as an “outdoor laboratory,” making use of steep gradients in temperature, precipitation, and land use. Their research combines large-scale biodiversity studies with detailed field experiments to reveal how global changes influence ecological processes and ecosystem functioning.

During my internship I became part of the DURIN project, which studies dwarf-shrubs (Ericaceae) – a dominant plant group across boreal, alpine, and Arctic ecosystems. Although small and often overlooked, dwarf-shrubs play a surprisingly important role. They provide food and habitat for many animals, support pollinators, and form symbiotic relationships with fungi (ericoid mycorrhiza), which are crucial for carbon sequestration and long-term carbon storage in soils. In the context of climate change, dwarf-shrubs are especially interesting because they can both expand and decline in response to shifting conditions, influencing large-scale processes such as “Arctic greening” and “Arctic browning.”

The aim of DURIN is to better understand how climate change affects dwarf-shrubs and, in turn, how these plants contribute to feedbacks between terrestrial ecosystems and the global climate system. This knowledge will eventually be integrated into land surface and earth system models to explore how dwarf-shrubs influence and contribute to vegetation–climate feedbacks.

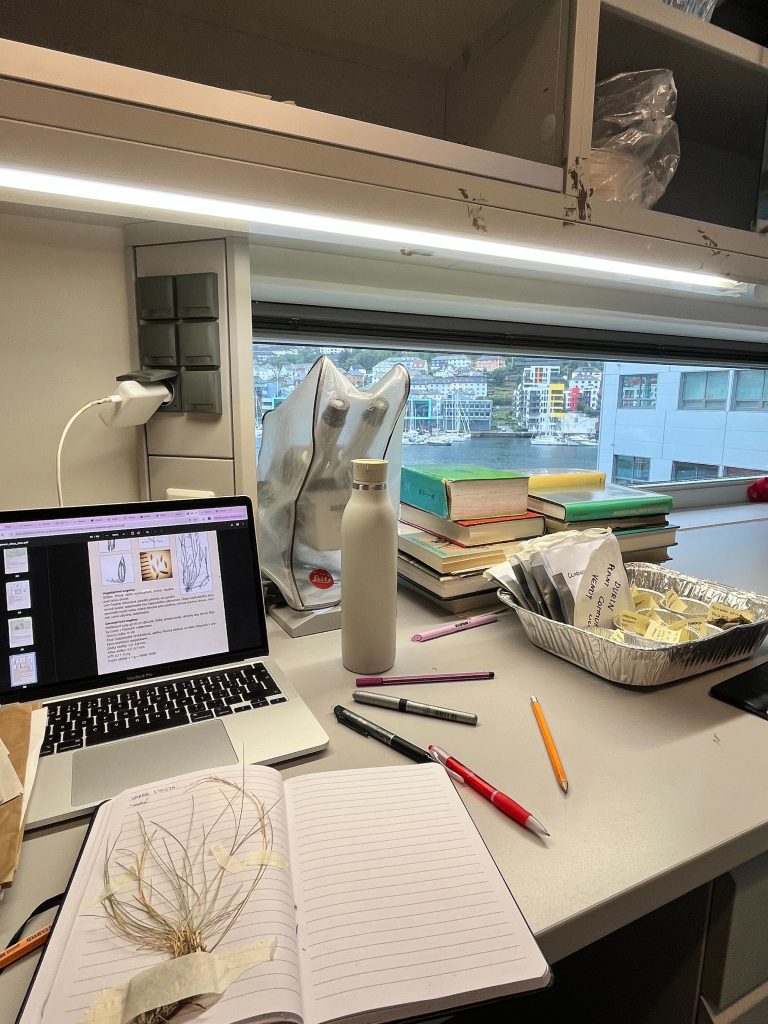

My specific role within the DURIN project focused on plant community composition. This part of the project involved recording the composition of plant and lichen communities and finally preparing a herbarium of all identified plants to be added to the museum collection. I was given this responsibility mainly because of the experience I had gained during my Bachelor thesis research. However, I would like to emphasize that such prior experience is not essential to apply for an internship like this. An internship is meant to be a learning opportunity – most of my tasks were completely new to me, and I received thorough training just like the other interns.

In addition to vegetation surveys, I took part in a wide range of activities: measuring carbon stocks and flows of the coastal heathland ecosystem, collecting and measuring thermal tolerance of leaves‘ photosyntetic response, measuring tree and shrub heights and diameters, biomass removal, measuring plants traits on focal dwarf shrubs species such as LAI (leaf area index), NDVI (value showing how ‘green’ and healthy the plants are, based on how much light they reflect), stem length, plant height, etc. I also helped with soil measurements and data collection for further analysis – such as soil depth, sense of clay, and collecting litter bags for ericoid mycorrhizae analysis. I was also involved in laboratory work, including biomass sorting, and in office tasks, such as data entry. Thanks to this variety of tasks, I was able to gain practical experience in both fieldwork and laboratory work.

Since most of the internship revolved around outdoor research, the interview process focused primarily on fieldwork skills: the ability to handle demanding conditions such as long days in the field, mosquitoes, and unpredictable weather. Equally important was the ability to work in a team, to ask questions when needed, and – most importantly – genuine enthusiasm for science. In my experience, it is this combination of curiosity, motivation, and supportive colleagues that carries you through the challenging but incredibly rewarding days in the field.

The DURIN project is based on four main field sites that represent a climatic gradient (continental/oceanic, northern/southern): in the north Senja and Kautokeino, and in the south Lygra and Sogndal. I had the chance to visit all of these sites during my internship. Even more importantly, all field trips were fully covered by the project grant – including transport (with flights to Northern Norway), accommodation, and food. This financial support was crucial, as I eventually spent more than half of my internship time in the field.

For me, it was – and still is – an incredible experience. Boarding a plane with a research team and scientific equipment to fly far above the Arctic Circle was something I had never even dreamed of. We had an amazing group of people, and the long journeys and shared living made us bond very quickly. After over two weeks working and living together, you truly become a team. Outside of fieldwork we went swimming in the fjords and enjoyed the breathtaking Norwegian landscapes – experiences I will never forget.

This internship gave me the chance to see some of the most beautiful places in Norway and to work alongside people who are truly leading experts in their field, such as Professor Vigdis Vandvik. I became much more confident in my ability to identify plants, and I learned an incredible number of new skills, both in the field and in the lab. Most importantly, I discovered what it really means to be part of a scientific team: how much work lies behind every project, every dataset, and every published article. I experienced first-hand what it means to be a scientist – and that was the main goal of my internship.